Investor-State disputes in the EU —

Some statistical observations

There is a common perception that investor-State disputes tend to happen only in emerging markets. To dispel this misconception, we analyse the most recent statistics available from the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) Secretariat concerning investor-State disputes brought against European Union (EU) Member States and/or brought by investors from the EU.

ICSID Caseload Report with a special focus on investor‑State arbitration in the EU as of April 30, 2017 offers an interesting overview of disputes involving EU Member States and investors, including the number of cases registered against each Member State, the number of cases brought by EU investors, the type of cases registered, the basis of consent to ICSID jurisdiction, and the economic sectors involved in each instance.

In this article, we review the key statistics from the report, compare prior ICSID Caseload Reports to ascertain trends, and discuss economic factors that have led to increases in ICSID cases involving EU Member State parties or EU investors.

EU Member States feature prominently in investor-State disputes

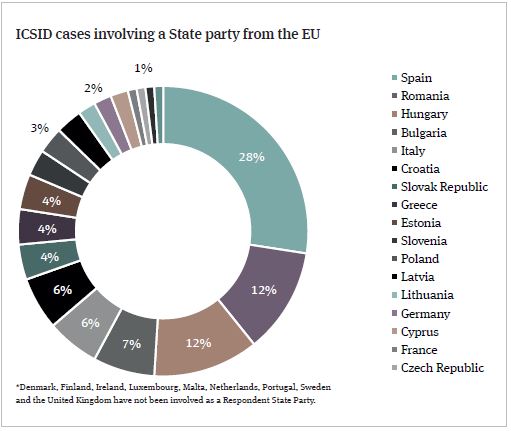

Despite the perception that investor‑ State disputes tend to happen elsewhere, in fact in 2017 a significant number of investor‑State cases included EU Member States: 105 of the 608 cases registered with ICSID (17 percent) involved an EU Member State as respondent to the claim. Spain had the highest number of recorded ICSID cases against it (28 percent), followed by Romania (12 percent) and Hungary (12 percent).

By comparison, ICSID’s 2014 EU Caseload Report recorded only 12 percent of cases as being against EU Member states. The most dramatic spike is seen in the number of cases against Spain, which increased from just over 11 percent to 28 percent of total cases registered. This increase is primarily due to the Spanish government withdrawing the incentives offered to new investors in wind energy, solar energy and waste incineration after the global recession hit its public finances. EU Member States such as Spain, the Czech Republic and Italy had strongly promoted policies subsidising investments in renewable energy pursuant to the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) objectives, but had to scale back those commitments because they could not meet the demand for subsidies after the economic crisis. In response, several groups of investors commenced arbitration against those States under the ECT challenging the withdrawal of their renewable energy subsidies.

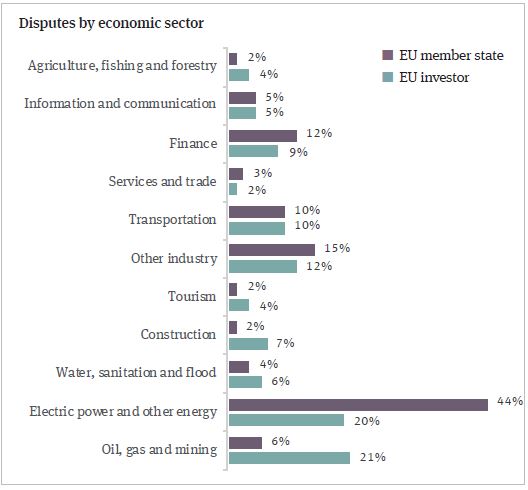

Most EU-related disputes involved the energy and extractive industries

By far the sector most represented in claims against EU Member States was the Electric Power and Other Energy sector with 44 percent of the cases registered involving that sector. The percentage of Electric Power and Other Energy sector disputes against EU Member States has risen dramatically since 2014 from 24 percent, again due to the ECT claims brought against EU Member States in response to the withdrawal of renewable energy subsidies. Similarly, 20 percent of cases brought by EU investors related to this sector.

Oil, Gas and Mining also featured heavily for EU investors (21 percent), although unsurprisingly not in respect of cases brought against EU Member States: only six percent of claims against EU Member States related to this sector.

The majority of claims were brought under bilateral investment treaties or the Energy Charter Treaty

The vast majority of all registered cases (97 percent) were brought under the ICSID Convention. In cases brought against EU Member States, the most common grounds for establishing ICSID jurisdiction were either bilateral investment treaties (BITs) (56 percent) or the ECT (43 percent). Compared to the figures in the ICSID’s 2014 EU Caseload Report, ECT disputes have risen considerably from 25 percent. Again, this spike is principally attributable to claims brought in response to the withdrawal of renewable energy subsidies.

For cases brought by EU investors, the basis of consent was predominantly BITs (61 percent), with the ECT representing a smaller proportion (15 percent), followed by investment contracts (14 percent) and host‑State investment laws (10 percent).

Disputes were more frequently resolved by a final award rather than a settlement

Settlement continues to play an important role in resolving investor‑ State disputes. 22 percent of cases against EU Member States were settled by the parties or discontinued before a final determination. This has decreased somewhat, with ICSID’s 2014 EU Caseload Report recording that 36 percent of cases settled or were discontinued.

Of the remaining 78 percent of claims against EU Member States that were resolved by a final award, 47 percent of cases were dismissed in full, whereas 31 percent of cases were upheld in part or full. Jurisdiction was declined in 22 percent of cases.

In comparison, 35 percent of cases brought by EU investors were settled by the parties or discontinued before a final determination. Of the remaining 65 percent of cases that fell to be decided by a tribunal, 25 percent were dismissed in full, whereas 49 percent of investors’ claims were upheld in part or full. Jurisdiction was declined in a similar number of cases (26 percent).

Arbitrators from the UK and France were chosen to preside over a significant proportion of cases

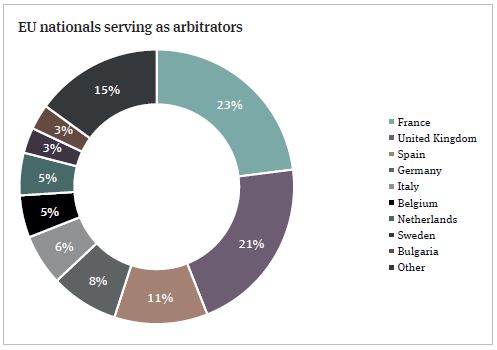

In approximately 72 percent of arbitral appointments made in ICSID cases, the parties selected the arbitrators, with ICSID appointing only 28 percent. In both scenarios, arbitrators from EU Member States were regularly appointed in a large proportion of investor‑state disputes.

43 percent of all arbitral appointments in ICSID cases involved nationals from an EU Member State, a level that has been consistent for the last three years. Nationals from France and the UK continued to be the most commonly appointed, followed by Spain, Germany, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Considering ICSID’s statistics in the context of proposed reforms of ISDS

Bilateral or multi‑lateral investment treaties (and sometimes free trade agreements) often offer important protections to foreign investors designed to help mitigate political risk, including detrimental regulatory change. The number of claims brought against EU Member States, evidences the fact that political risk is not an issue solely found in emerging markets. If an investment is structured appropriately, investors into the EU (whether from outside the EU or other EU Member States) can benefit from these important protections, as can EU Member States given that the existence of such protections, in turn, helps promote foreign investment.

Arguably the most important protection is the right of foreign investors to bring proceedings against a host‑State in a neutral forum (generally, international arbitration seated in a neutral State).

Without that, the only recourse available to foreign investors would be to seek to bring a claim before the domestic courts of the host‑State, or hope to persuade their home State to seek a diplomatic State to State resolution. Neither of those options historically proved particularly effective or satisfactory for foreign investors, hence the development of ISDS. Yet despite this, a number of States across the globe are now seeking to modify or remove these protections. These reforms are largely a reaction to the backlash against ISDS by critics of the system.

A number of States have terminated their investment treaties or sought to amend them to remove ISDS provisions. The EU plans significant reforms to ISDS (as discussed in a prior article in issue 8 of the International arbitration report) and a number of other States are following suit. The level of investor‑State disputes involving EU Member States and/or EU investors puts into context how significant these reforms will be to both EU investors and investors into the EU.

ISDS is admittedly not a perfect mechanism (though it is hard to find any perfect dispute resolution mechanism) but most critically for investors, as things currently stand, there is no effective, viable alternative and reforms proposed to date seem likely to bring their own issues. Only time will tell if in the mid to long term this will impact foreign investment into those States — whether by reducing investment or making it less profitable as investors are forced to mitigate the risk of their investment in other ways.

The key takeaway for foreign investors, however, is that these are important developments which will have a direct impact on them. It is important that investors follow these trends, and ensure that they have a voice in the ongoing debate about changes to the current system for resolving disputes between foreign investors and the host‑States that they are investing in.

With special thanks to Aimee Denholm, Knowledge assistant, for her contribution to this article.

Featured

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .