Myanmar is one of the world’s oldest oil producers; exporting its first barrel of crude in 1853. Despite this, its upstream sector is still in its infancy. This is due to a number of factors: sanctions, opaque regulatory policy and insufficient investment have all hindered Myanmar’s efforts to realise its oil and gas potential. Since the lifting of sanctions by the US and European Union in 2012, Myanmar has taken active steps to reform its foreign investment laws and has held a number of successful international bid rounds for onshore and offshore oil and gas blocks.

In 2014 Myanmar attracted foreign direct investment totalling US$8 billion, of which more than 35 per cent was generated by the energy sector. E&P companies are attracted by the undoubted potential Myanmar offers. Although, proven energy reserves are still relatively modest, unofficial estimates are extremely promising and those, together with proximity to some large demand centres in Thailand and China have attracted the interest of several major players.

Below we consider the ten things foreign investors looking to invest in Myanmar’s oil and gas industry should know:

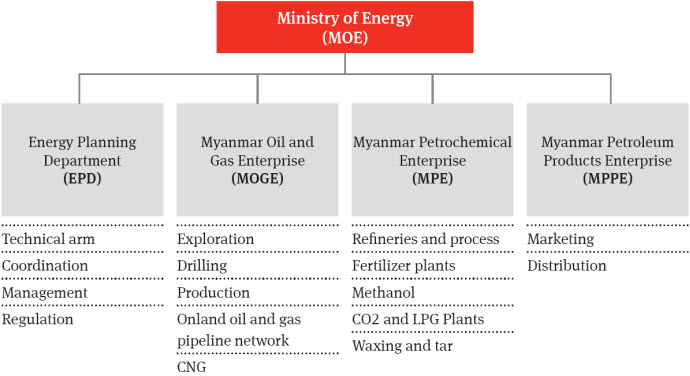

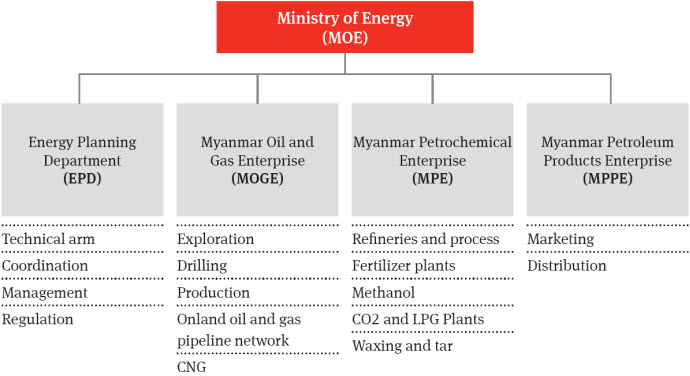

01 |Government structure

The Ministry of Energy (MOE) is the coordinating body for all types of energy in Myanmar. The MOE has oversight of four state-owned enterprises/departments:

In addition to the above organisations, in January 2013 the National Energy Management Committee was established with a mandate to streamline Myanmar’s energy policy. The National Energy Management Committee is comprised of the MOE, the MOGE and ten other governmental institutions involved in energy development.

02 |Legal and regulatory framework

Myanmar has several oil and gas related laws, all largely based on British Law Codes of pre-independence Indian Acts. However please note that contrary to the licensing regime of the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ model, a production sharing contract (PSC) is entered into between the MOGE and the relevant foreign investor. For the more explored onshore blocks improved petroleum recovery contracts (IPR) have also been entered into, with three being awarded in the 2013 international onshore bid round. Provided that a conflict with an existing law does not exist, the terms and conditions of such contracts will govern the foreign investor’s rights and obligations.

Foreign investors should be aware that the number of Government entities required to review and approve the PSC is extensive and includes: the MOGE; the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development (MNPED); the Contract Department of the Attorney General’s office; the Ministry of Finance; the Myanmar Investment Commission (MIC); and the Ministry of Environmental Conversation and Forestry.

03 |The duration of the model PSC

The onshore model PSC has three phases, the Preparation Period, the Exploration Period and (if any) the Development and Production Period. The offshore model PSC has an additional phase: the Study Period.

Preparation period

The Preparation Period is for a six month duration, which can be extended at the discretion of the MOGE. During this period the Contractor is required to commission (i) an Environmental Impact Assessment, (ii) a Social Impact Assessment and (iii) an Environmental Management Plan (the Reports). The preparation of these Reports will count towards to the exploration minimum expenditure requirement. Once the Reports have been prepared they must be approved by the MIC before petroleum operations can commence.

Study Period (for offshore PSCs only)

In Myanmar, while much is known about the onshore geology, there is very little seismic data available for offshore blocks. The Study Period provides the Contractor two years to conduct technical evaluations and assessments prior to the Exploration Period. The model PSC anticipates that there will be a minimum work commitment during this period, but does not specify the amount. The Contractor must disclose all the results of its study to the MOGE. At the end of the Study Period the Contractor may, at its discretion, terminate the PSC and relinquish its rights.

Exploration period

The duration of the Exploration Period is up to six years:

Three years (Initial Exploration Period) + two years (First Extension Period at Contractor’s option) + one year (Second Extension Period at Contractor’s option).

Unlike PSCs in many other jurisdictions there is no phased relinquishment during the Exploration Period. Instead relinquishment occurs at the end of the Exploration Period and amounts to 100 per cent of the contract area, less any discovery area, development and/or production area. In addition, there is an automatic extension of the Exploration Period to allow for completion of seismic or drilling operations or to appraise a discovery.

Development and Production Period

The Development and Production Period commences on the date the Contractor gives notice of a commercial discovery to the MOGE and shall continue to the later of: (i) twenty years from the date of completion of development in accordance with Development Plan, and (ii) the expiration of the petroleum sales contract.

04 |Foreign investment structure

The new Law of Foreign Investment (the FIL), which repeals the previous 1988 Law of Foreign Investment, was enacted in November 2012. The MNPED is the government ministry responsible for foreign investment and the MIC is the regulator responsible for approving foreign investment in Myanmar.

The FIL requires foreign investors to:

- establish a branch or subsidiary (although a branch is more common)

- obtain an MIC permit and trading permit

- obtain a certificate of registration as a branch.

An oil and gas investor must be recommended by the MOE before it can receive a permit from the MIC. The MOE is required to makes its recommendation within seven days of the receipt of a recommendation request and the MIC must grant or refuse the permit within ninety days of the date of receipt of the MOGE. In addition the MOE will manage the MIC permit application process, whereas this would be the foreign investor’s responsibility in cases not involving oil and gas.

05 |Local partners

The FIL places a requirement on foreign investors holding an interest in onshore and offshore shallow water blocks to cooperate with a local partner. For onshore blocks, foreign investors are required to cooperate with one of the approved, registered domestic entities listed on the website of the Ministry of Energy. For offshore shallow water blocks a foreign investor must co-operate with, as a minimum, one national company registered with the EPD. No cooperation is required in offshore deep water blocks due to the high costs and technical expertise required.

The level of the local partners’ participation and the form such contribution will take is a commercial decision and is not specified by law. A foreign investor, when negotiating the local partner’s contribution should take into consideration the intention behind this legal requirement, which is to increase the level of experience and knowledge of the local oil and gas industry in Myanmar.

The foreign investor and the local partner will generally sign a memorandum of understanding and subsequently a joint operating agreement (JOA). These agreements will set out the level of participation and the participating interest of the local partner, and the terms of the JOA must be approved by the MOE.

Given the strict penalties imposed on companies found in breach of the UK Bribery Act and US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the perceived high level of corruption in Myanmar (see paragraph 10 below) a foreign investor should have a clear understanding of who they are dealing with (particularly given the pervasiveness of the military in commercial and governmental enterprises) to avoid inadvertently violating such laws and should conduct extensive due diligence on local partners and their business associates.

06 |Farm-in opportunities

Following the recent international bid rounds, a number of successful bidders are considering opportunities to reduce their risk exposure through farm-in arrangements. An investor seeking to farm-in should be aware of the following:

- Model PSCs: the model PSCs for onshore and offshore that are commonly used in Myanmar contain a number of important provisions that have caused foreign investors some concern. The MOE however, was only willing to consider amendments to the commercial terms of the model PSCs. Proposed amendments to legal terms of the model PSCs were largely resisted by the MOE who wished to keep the executed PSCs consistent. At the time of writing this briefing all but one of the twenty offshore blocks awarded in March 2014 have been signed – the success of the Contractors in negotiating amendments to the model PSCs, however, remains to be seen.

- Management Committee: MOGE retains rights of management for petroleum operations, but recognises that the Contractor is responsible for the execution of the work programmes. The model PSC requires the Contractor to establish a Management Committee which will have overall supervision and operator management of the petroleum operations. The Management Committee will consist of four representatives appointed by the MOGE, one of whom will act as Chairman and three representatives appointed by the Contractor. The quorum of the Management Committee will be one representative appointed by the MOGE and one representative appointed by the Contractor. All decisions required to be taken by the Management Committee shall be taken by unanimous vote of the representatives present at the meeting. If the Management Committee cannot reach a decision, the MOGE Managing Director will make the final decision.

- Tax: many foreign investors in Myanmar’s oil and gas industry are incorporating SPVs in Singapore who will then establish a branch and then enter into the PSCs with the MOGE. A key reason for this is that Singapore has a double taxation treaty with Myanmar, which allows for repatriation of profits.

- Government approval: as detailed above, government approval and recommendation from the MOE is required in order for a foreigner to invest in oil and gas in Myanmar.

07 |Royalty, state participation and other associated costs

Signature bonus

A signature bonus is paid by the Contractor within thirty days of signing the PSC. The amount of the signature bonus is not specified in the model PSCs and is generally a matter of commercial negotiations.

Royalty

A royalty is payable at the rate of 12.5 per cent of ‘Available Petroleum’ i.e. petroleum produced and not used in petroleum operations. The royalty is not recoverable from ‘Cost Petroleum’ (defined below).

Production bonuses

The model PSC provides for production bonuses payable following commercial discovery and thereafter at defined production rates. The production bonus is a progressive per rate of production – US$0.5 million to US$6.0 million for onshore blocks, and US$1 million to US$10 million for offshore blocks.

Guarantee

The Contractor is required to provide a parent company guarantee and a performance bank guarantee in the form set out in the model PSC. The performance bank guarantee equates to 10 per cent of each minimum commitment phase. The MOGE will release the performance bank guarantee no later than twenty days following the date of completion of the respective period. The parent company guarantee requires the parent company to discharge all obligations of the Contractor upon the Contractor’s failure to perform. The risk with this form of guarantee is that the parent company could be seen to be guaranteeing all of the Contractor’s obligations, not just the minimum work commitments. Unfortunately as far as we are aware, the MOGE has been unwilling to accept limitations to this guarantee on the premise that it wishes all parent company guarantees and performance bank guarantees to have the same terms.

State participation

The MOGE has the option to take an interest of 15 per cent to 25 per cent in onshore blocks, and 20 per cent, with the right to increase to 25 per cent if the reserve is greater than five trillion cubic feet on a BOE basis, in offshore blocks. This right is exercisable within three months of the Contractor’s notification of its first discovery. If MOGE elects to exercise its participation option, it must reimburse the Contractor for its portion of previously incurred and ongoing petroleum costs and its portion of the signature bonus.

Employment and training

The model PSCs contain typical provision regarding the employment of local personnel. Notification No. 11/2013 issued by the MNPED, which seeks to implement the FIL, also provides details on employment and training of local staff and the issuance of work and stay permits for expatriate staff. The model PSCs require Contractors to spend at least US$25,000 per year during the Exploration Period and US$50,000 during the Development and Production Period on training funds for onshore PSCs, and at least US$50,000 per year during the Exploration Period and US$100,000 during the Development and Production Period for offshore PSCs. In addition to contributing minimum funds to training, the Contractor must also establish a research and development fund and contribute 0.5 per cent of its share of ‘Profit Petroleum’ – all funds being recoverable from Cost Petroleum. The apparent lack of transparency and objectivity in the allocation and use of these funds however, has caused some Contractors concern.

Cost recovery

Cost recovery is limited to ‘Cost Petroleum’, which is a maximum of 50 per cent of available petroleum for onshore blocks, 60 per cent for offshore blocks and 70 per cent for offshore blocks exceeding a water depth of 2,000 feet. Costs are generally recoverable when incurred or in the financial year in which commercial production occurs, whichever is later. If costs exceed the value of Cost Petroleum they can be carried forward to the next accounting period.

Domestic crude oil and natural gas requirement

The Contractor will be under an obligation to provide 20 per cent of crude oil production or 25 per cent of natural gas to the domestic market of the Contractor’s share of Profit Petroleum (i.e. after deduction of royalty and costs). The MOGE is required to pay the equivalent of 90 per cent of the fair market value in US dollars. We understand that delays in receipt of payment from MOGE have been a major issue for some onshore producers.

08 |Change of control

The Contractor may assign its rights under the PSC to an affiliate or, with prior written approval of the MOGE (not to be unreasonably withheld), to other third parties. On assignment the Contractor will be liable to pay income tax based on the capital gain in accordance with the following rates:

| Capital gain | Income tax rate |

|---|

| 1. up to an amount equivalent to MMK100,000 million | 40% |

| 2. an amount equivalent to from MMK100,001 million to MMK150,000 million | 45% |

| 3. an amount equivalent to MMK150,001 million and above | 50% |

The model PSC does not state if the payment is tax or capital gains tax. It is therefore, unclear as to whether this payment is subject to Myanmar’s double taxation agreements. We understand that the Ministry of Finance, on a discretionary basis, gave clarity on this point to those Contractors who requested it.

Prior to March 2014, capital gains in the model PSCs made reference to US dollar tax brackets rather than the Myanmar Kyat. Following the implementation of Union Tax Law 2014, capital gains will now be calculated using the Myanmar Kyat (in accordance with the table above). Currency fluctuation and inflation in Myanmar Kyat may therefore, lead to uncertainty in farm-out arrangements. Such uncertainty will need to be addressed in the commercial agreement reached between the farmor and farmee.

09 |Governing law, dispute resolution and inalienable rights

The model PSCs are governed by the laws of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. The model PSC for offshore blocks provides for disputes to be settled in accordance with the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, in front of three arbitrators in Singapore. Myanmar acceded without reservations to the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitration Awards 1958. Once the Government implements the convention by adopting domestic legislation, the Myanmar courts will be obliged to give effect to any foreign arbitration clause and to enforce arbitral awards made in other member states.

Conversely the model PSC for onshore blocks provides for arbitration conducted under the Myanmar Arbitration Act, 1944 (Myanmar Act IV, 1944). This is far from ideal – the 1944 law is extremely outdated and generally unsuitable for modern day arbitrations. The MOGE had previously indicated that Singapore arbitration under UNCITRAL might be possible for onshore PSCs. However we understand that this was met with opposition from the Attorney General and the MOGE decided not to deviate from the model PSC for onshore blocks.

The model PSCs state that nothing in the PSC shall prevent or limit the Government of Myanmar from exercising its inalienable rights. The concept of ‘inalienable rights’ is not defined. The concern is that this could give the Government of Myanmar the right to set aside the entire PSC if a right contained in the PSC was found to be inconsistent Myanmar’s inalienable rights. We understand that this requirement was inserted in the model PSC at the request of the Attorney General and so is unlikely to be removed in the executed PSCs.

10 |Anti-corruption

Myanmar is perceived as having a high level of corruption, the Transparency International’s (TI) Corruption Perceptions Index, which ranks countries based on how corrupt the public sector is perceived to be, ranked Myanmar 156 out of the 175 countries surveyed in 2014. In the past Global Witness, a UK based advocacy group, has been highly critical of Myanmar’s oil and gas sector, has described it as highly secretive and warned that state revenue could be lost to corruption. However, in July 2014 Myanmar became a candidate member of the ETIT, a global standard under which governments and companies agree to report how much is paid for extracting natural resources. Further, in October 2014 Global Witness confirmed that more than half of the companies who won major oil and gas blocks in Myanmar have declared their ownership structure, setting a ‘global precedent’.

Myanmar has a patchwork of legislation relating to corruption and bribery which has been a crime since the Suppression of Corruption Act in 1948. Myanmar signed and, in 2012 ratified, the United Nationals Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC). Pursuant to its obligation under UNCAC to implement anti-corruption legislation, Myanmar enacted the Anti-Corruption Law in 2013. This law is aimed at the eradication of bribery and provides a more coherent approach than the previous patchwork of laws in relation to corruption that were in place. While this law generally prohibits the bribery or acceptance of bribes by public officials in Myanmar, it is too soon to assess the extent to which it will be actively enforced.

Companies undertaking business in Myanmar should exercise caution to avoid inadvertently violating local anti-corruption laws as well as the laws of other jurisdictions with extraterritorial effect. To the extent possible companies the UK Bribery Act 2010 requires the conducting of meaningful due diligence on agents, intermediaries and joint venture parties when entering into, and throughout the course of, a business relationship. Companies not under the jurisdiction of that Act may still regard the exercise as prudent.

Contacts

Ashley Wright

Partner

Tel +65 6309 5310

ashley.wright@nortonrosefulbright.com

Zoe Bromage

Associate

Tel +65 6309 5343

zoe.bromage@nortonrosefulbright.com

Contributing law firm

VDB Loi

Edwin Vanderbruggen

Yangon

Tel +95 1371902

edwin@vdb-loi.com

Jeffery L. Martin

Yangon

Tel +95 1371902

jeffrey.martin@vdb-loi.com